Over at his blog, Bogost has a great post up on human suffering and OOO, addressing the question of whether a posthumanist ontology (my term for it, not his) undermines our ability to address questions of human suffering, inequality, injustice, etc. The whole post is well worth reading, but I wanted to draw attention to one passage in particular:

Over at his blog, Bogost has a great post up on human suffering and OOO, addressing the question of whether a posthumanist ontology (my term for it, not his) undermines our ability to address questions of human suffering, inequality, injustice, etc. The whole post is well worth reading, but I wanted to draw attention to one passage in particular:

Indeed, taking for granted, in advance, what actors and approaches are of most appropriate use feels far more destitute as a philosophy than opening the floodgates. Mark Nelson has quippedthat “radical critique” involves applying well-worn tools in the conventional way to reach the expected conclusion. Contrary to popular belief, such an attitude looks far more like nihilism than it does like revolution, or even liberation. By contrast, the realist position recommends greater attention and respect, not lesser. It admits that we have to do the work of really looking hard at all the things in the world before drawing conclusions about what they mean for one another—or for ourselves. That’s not a poverty of philosophy, at all. Just the opposite. A wealth, a cornucopia, a profusion, almost to the point of overwhelm.

This is a common theme in Bogost’s work. What, he seems to ask, do our theoretical commitments blind us to? What other forms of engagement would open up for us if we suspended these a bit and instead looked at the role played by other entities in assemblages?

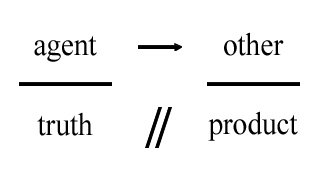

What Bogost seems to be critiquing is what Lacan called “the university discourse” (depicted to the right, above). For Lacan a discourse refers not to the content of a particular discipline, such as what Foucault analyzes in The Order of Things, but to a particular relation between an agent and an other. We have the agent addressing an other, producing a product. In the lower left-hand position we see “truth”. The truth of a discourse relation is it’s unconscious. It is what the discourse simultaneously excludes in order to function and that upon which it is based. There are four of these discourses; or, if you follow my work, 24 possible discourses (warning .pdf).

What Bogost seems to be critiquing is what Lacan called “the university discourse” (depicted to the right, above). For Lacan a discourse refers not to the content of a particular discipline, such as what Foucault analyzes in The Order of Things, but to a particular relation between an agent and an other. We have the agent addressing an other, producing a product. In the lower left-hand position we see “truth”. The truth of a discourse relation is it’s unconscious. It is what the discourse simultaneously excludes in order to function and that upon which it is based. There are four of these discourses; or, if you follow my work, 24 possible discourses (warning .pdf).

We shouldn’t take the term “university discourse” too seriously. “University discourse” doesn’t refer to particular institutions like Princeton and Oxford, but to a particular form of relation between an agent and an other. While university discourses often occur in universities, they also occur in corporations, governments, psychiatric clinics, living rooms, on blogs, etc. This sort of discourse structure can be exemplified in a variety of different places.

So what sort of relation is at work in university discourses? On the upper right hand we see the following relation: S2 —> a. In this context, we can read “knowledge” addressing an individual that is new and unknown. We might think of S2, for example, as the system of diagnostic categories in the DSM-IV. A person walks into a psychiatric clinic (the other, the unknown). The person describes what they’re suffering from: repetitive washing of the hands, fear that they are being watched, inability to get out of the bed, whatever. The psychiatrist now consults the DSM-IV and subsumes the person under the category of obsessional neurosis, paranoia, or depression. The symptoms are indexed to a system of categories or “knowledge” (S2). The case is similar when you fill out a form for Uncle Sam or the government. You’re given a list of options for your sex, ethnicity, and religion (S2) and must subsume yourself (objet a) under one of these categories. Likewise, in bad psychoanalysis, we get a university discourse in the sense that we always know (S2) that the patient will be suffering from an Oedipus complex, fear of castration, etc. Every new analysand learns exactly the same thing (S2) with only the details of the stories of castration and Oedipus changing. Another good example is Zizek’s work. We think we’re before an analyst’s discourse, but instead we’re before a machine that monotonously finds the same thing, again and again, in whatever cultural artifact he investigates. Far from an encounter with the enigma of something new, we instead have the endless subsumption of all things to his theoretical machine. We know exactly what we’re going to find: “the standard interpretation is x, but it is really y.”

We can basically call the “university discourse” what Kuhn called “normal science“. In “normal science” we don’t get a new theory, but rather we get the progressive subsumption of unexplained phenomena (objet a) under the “paradigm” (S2) or existing system of explanation and categorization. Marco Polo mentions that unicorns do, in fact, exist; they just have grey skin, two horns, are rather ugly and ill tempered, etc. He’s referring to his encounter with the rhinoceros. Marco Polo is here working in a university discourse, subsuming a new entity under the paradigm of animal classification he had available to him at the time. The comparison of the university discourse to normal science should disabuse us of the notion that university discourses are intrinsically bad things. A lot of new knowledge is produced through these things. They can be positive practices and debilitating ones.

We can basically call the “university discourse” what Kuhn called “normal science“. In “normal science” we don’t get a new theory, but rather we get the progressive subsumption of unexplained phenomena (objet a) under the “paradigm” (S2) or existing system of explanation and categorization. Marco Polo mentions that unicorns do, in fact, exist; they just have grey skin, two horns, are rather ugly and ill tempered, etc. He’s referring to his encounter with the rhinoceros. Marco Polo is here working in a university discourse, subsuming a new entity under the paradigm of animal classification he had available to him at the time. The comparison of the university discourse to normal science should disabuse us of the notion that university discourses are intrinsically bad things. A lot of new knowledge is produced through these things. They can be positive practices and debilitating ones.

Nonetheless, the foregoing gives a sense of why we see “$”, the matheme for the barred or alienated subject, appear in the place of the product of these discourses. In being passed through the sieve of S2, of the system of explanation or categories, objet a, the new case, is alienated in that system. It is not objet a that is generating new knowledge, but rather it is simply being subsumed under the existing system of categories as yet one more instance of a kind. This comes out clearly in the case of our discussion of the psychiatric clinic and bad psychoanalysis. The person (objet a) comes in, talks about their symptoms, and is immediately indexed to a diagnostic category in the DSM-IV. That category is then indexed to a particular treatment such as a suggested medication or course of therapy. What hasn’t happened is the speech of the patient. The patient hasn’t been given a space to articulate the meaning behind their symptom because that “meaning” is already assumed. What would the patient have to offer? Anything they say about, for example, their sense of being watched is immediately subsumed under the category of paranoia (the thought that this could be a hysterical form of desire is never even entertained). Hence they are “divided”– $ –from themselves and alienated in the system of categories. The DSM-IV always already knows. There can never be a question of a case that would disrupt or fundamentally fail to fit with that system of categorization and explanation. The same is true with bad psychoanalysis. Whatever the analysand says, the analyst always already knows that it will be a case of castration and the Oedipus. All enunciations, all symptoms, are immediately indexed to the family drama.

Nonetheless, the foregoing gives a sense of why we see “$”, the matheme for the barred or alienated subject, appear in the place of the product of these discourses. In being passed through the sieve of S2, of the system of explanation or categories, objet a, the new case, is alienated in that system. It is not objet a that is generating new knowledge, but rather it is simply being subsumed under the existing system of categories as yet one more instance of a kind. This comes out clearly in the case of our discussion of the psychiatric clinic and bad psychoanalysis. The person (objet a) comes in, talks about their symptoms, and is immediately indexed to a diagnostic category in the DSM-IV. That category is then indexed to a particular treatment such as a suggested medication or course of therapy. What hasn’t happened is the speech of the patient. The patient hasn’t been given a space to articulate the meaning behind their symptom because that “meaning” is already assumed. What would the patient have to offer? Anything they say about, for example, their sense of being watched is immediately subsumed under the category of paranoia (the thought that this could be a hysterical form of desire is never even entertained). Hence they are “divided”– $ –from themselves and alienated in the system of categories. The DSM-IV always already knows. There can never be a question of a case that would disrupt or fundamentally fail to fit with that system of categorization and explanation. The same is true with bad psychoanalysis. Whatever the analysand says, the analyst always already knows that it will be a case of castration and the Oedipus. All enunciations, all symptoms, are immediately indexed to the family drama.

We thus see why S1 appears in the position of truth in the university discourse. It is the unconscious of this discourse. S1 is the signifier for power, mastery, completeness, the father, God, the master, etc. It is a being or signifier that would somehow manage to escape the diacritical play of signifiers and ground identity and a foundation absolutely. S1 appears in the position of truth for two reasons: First, discourses of the university always seem to refer to some master figure (S1) that functions as the foundation of the discourse and its guarantee: Freud, Lacan, Marx, Adorno, Deleuze and Guattari, Einstein, etc. The master is uncastrated or truly knows (the relationship between God and the claims of the Bible, for example), and therefore the system of categories cannot be mistaken. Yet if the relationship to the master must be in the place of the unconscious, then this is because the system of knowledge (S2) must present itself as objective and impartial. It can’t make an appeal to authority to ground itself because then it would reveal its circularity. But more fundamentally, S1 appears in the place of truth, the unconscious, then this is because university discourses are generally premised on a will to mastery, control, and power. Lacan liked to say that we have a desire for ignorance, that we don’t want to know anything about “it”. What we really want is a world where all the pegs fit in the holes and there’s nothing noisy or aleatory. We certainly don’t want to listen to objet a and allow it to disrupt our S2.

When I hear Mark Nelson and Bogost claim that critical theory uses well worn theory to reach expected conclusions, I hear them basically saying that critical theories are all too often university discourses. Far from being emancipatory, far from surprising us, we instead know exactly what we’re going to find: that x is “ontotheological”, or x is animated by a “sickening jouissance”, or that x is a neoliberal capitalist ploy, or that x is a form of religious superstition, or that x is this, or this, or this, or this. We begin from the premise that whatever cultural phenomena we encounter, whatever artifact we encounter, etc., is already subsumable under our categories and explanatory frameworks (S2). And inevitably, this is premised on some fidelity to a master (S1) and will to power (S1) in a world that is pretty chaotic (objet a). In a move that is worthy of Laruelle (one of the latest S1’s), we can say that critical theory perpetually posits the being of the real and is endlessly caught in a form of analysis based on its own arbitrary decision ultimately based on fidelity to a master; a fidelity that thoroughly contradicts the rejection of mastery taught by all of these figures. With the exception of true Lacanians like Guattari, for example, we seldom do what these masters themselves did: listen to objet a, to the unassimilated, as the only source of knowledge rather than subsuming it under a category. We seldom surrender mastery and open a space where we might be surprised and discover that something very different is going on. Instead, we always already know what we’re going to find as a function of our critical apparatus. Yet the worst thing about this sort of theoretical practice is that, like the fundamentalist Catholic theologians, it seems obsessed with finding sin everywhere. Everything must be shown to be dirty. Everything must shown to be compromised. Seldom do we encounter a form of practice that is for something. Indeed, the very act of being for something is seen as naive and suspect.

December 12, 2012 at 3:33 am

Yes! This is much better articulated than my 2-year-old tweet above, which has gotten occasionally retweeted and quoted more than I expected (it was, after all, an off-the-cuff, <140-char quip, intended to be read by approximately nobody).

It comes off as a bit reactionary to me reading it standalone like that, but at the time my annoyance was directed at a certain academic discourse that it seemed like went rather ironically under the name “radical critique”, because naively I would expect to be shocked or surprised by something termed “radical”, but the articles often seemed predictable, like a grad student faithfully applying what they learned in class. No doubt, any one instance of it might shock someone completely unfamiliar with the whole genre: there are people who are shocked as soon as an essay says “Marx” or names “capital”, and there are still people who have no clue what a term like “trans” might even mean. So maybe it’s fair as shorthand for, “the genre of writing that an average American may find too radical for them”. But if the problem is that we have good critiques that not enough people are reading and which aren’t producing any revolutions, it’s not clear to me the solution is to keep re-applying the same machinery to more instances.

I also tend to think of the American version in particular, where French Theory, unlike in Actual France, has a sort of mystical, wisdom-beyond-the-seas aspect to it, where we wait for translations and then faithfully apply the learnings from each wave of enlightenment. Apparently even theorists like Julia Kristeva are surprised and somewhat befuddled by this aspect of their reception in the US. So maybe things are different/better/worse elsewhere.

December 12, 2012 at 8:29 am

This is a wonderful post.

“With the exception of true Lacanians like Guattari, for example, we seldom do what these masters themselves did: listen to objet a, to the unassimilated, as the only source of knowledge rather than subsuming it under a category. We seldom surrender mastery and open a space where we might be surprised and discover that something very different is going on.”

Is this at least in part what Foucault was getting at when he called Ant-Oedipus a guide to non-fascist living? (I’m not referring to Foucault here as a master, I hope, but just as the source of a quote)

As for “radical critique” I like what Mark N says, “it’s not clear to me the solution is to keep re-applying the same machinery to more instances.” This always happens, that repetition loses content, like a xerox of a xerox of a xerox (just wait til the generation of object oriented philosophers 30 years for and you’ll be shuddering the same shudder). But it wouldn’t be fair, I think, to subsume Adorno or Benjamin or Bloch, say, under this debase notion of radical critique, since it’s their epigones who are doing the re-applying. Those guys were *listening*, just as Guattari was.

December 12, 2012 at 12:30 pm

As so often I find myself nodding in vigorous agreement! Have been reading & am very excited by Laruelle, & I love the simplicity of his idea of being caught in the kind of self-referential circle that you also describe above. However, I can not shake the sense that Laruelle too is ultimately trapped in the same double-bind (as Michael Olson also argues in his chapter of Laruelle and Non-Philosophy; claiming that Laruelle is stuck between philosophy (using/cloning philosophical concepts) & his axiomatic positing of the Real as radically indescribable). Still, Laruelle’s idea of a general science or practice is very appealing to me; attempting to describe situations from the bottom up, as expressions of the Real, & not top-down, from an already established paradigm. Practising/thinking alongside, or as you suggest, for the object of observation, instead of fitting into the straightjacket of predetermined concepts. & I do think non-philosophy is an admirable attempt, but practically (especially for me, doing literary theory & not pure philosophy) I wonder how different it is from, for example, your method of bricolage, of always trying to find the right concept for each new situation; or Karen Barad’s hyper specific materialism. However, I wonder how it is possible to really practice an immanent aesthetics or ethics; that is, to really each time derive a new vocabulary from the specifics & singularity of each situation, without falling back on existing paradigms/concepts. I guess that is the difference between representation & performativity (Karen Barad for example has a great essay about this difference, & she has another essay that really performs this difference, it enacts its content (indeterminacy) in its form (e.g by its is non-linear structure)). As the poet Robert Creeley famously wrote (& many others have echoed in different ways), “Form is never more than an extension of content.” I wonder if you could say more about how to practically avoid representation / University discourses? I guess that is also what appeals to me about Laruelle (even if he does seem stuck in a similar self-referential circle with which he describes philosophy), his emphasis on practice instead of theory. Either way, thanks, as always for your very inspiring & lucid posts!

December 12, 2012 at 2:06 pm

I should probably apologize to Mark for pilfering his one-liner as a robust position. I too really appreciate this more detailed articulation of the idea.

December 13, 2012 at 2:42 am

This reminds me of the Lacan quote “If you can understand an interpretation, then it is not a psychoanalytic interpretation.” That is to say, the purpose of interpretation is not to be recognizable, but to disrupt the very process of recognition itself. We go into analysis ready to recognize, and if the analysis is to be actualized, it must disrupt our constant (mis)recognition.

One problem, though, is that the recognition of structural isomorphy is itself recognition of this type: complex equivalence which says “this is that.” Even if I say “this idea which you presented _is_ this other idea which I present” it is merely because I recognize in your idea something which fits into my preconceived beliefs. So I can find agreement with you and end up even feeling some sort of narcissistic elation or validation that someone else agrees with me — even if this agreement is based on my own misrecognition of an ostensible affinity between our concepts.

December 13, 2012 at 4:10 am

Despite the piece is nicely written, full of engagement, and despite on the surface it appears quite reasonable I don’t agree. The main reason is the structure on the delocutionary level. And this structure is basically scholastic.

First, I would agree to the result of your anamnesis that there is a problem with “normal science”, and by analogy, “normal critical thinking”, albeit I clearly reject Kuhn’s wording of “normality” here.

Secondly, I would also agree with your diagnosis that there is kind of a ‘binding problem’. Listening to patients tells a quite different story than could be learnt in arrogant circles, largely detached even from the clouds they produce.

Yet, I also sense a somewhat deeper conflict in your argumentation regarding the problematic field between theory, performance, model and operation (politics). The mutual relations between those are characterized by fractal differentials, while at the same time the clear distinction between the outside and the inside looses its meaning.

Precisely this distinction you seem to try to keep in charge. Even more, you construct a dialectic (empirical vs theoretical, or hands-on vs. palaver-only) that you quickly describe as pathological. Both moves together, the neglect of the fractal differential and the simplistic upper-lower-level-mechanics result in a scholastic structure.

Of course, I don’t want to defend any of the guys like zizek, negri, harmann etc. Yet, the reason for their failure is not what you call “university discourse” in your diagnosis. The reason is the said ‘binding problem’: From the conceptual level the question is “How to get into action?”, while for the operational level (revolutionary?) it is “How to get informed by which (kind of) concepts?”

Neither listening, nor writing books, nor enforcing people to read dissolves the blockade. After all, what zizek & co, but also you, seem to overlook is the particular quality of model (implying measurement) and method (implying instrumented experimentation), which are implied for both directions, from concept to operations as well as the reverse direction.

Obviously, a critical, and unresolvable, ethical dimension is implied here. But it is also clear that empirical activities (“listening”) can’t do without concepts.

Neglecting the binding problem is all too easy for the flat worlds of materialists and scholastics, of course. In any case, a characteristic pathology regarding the arguments will show up. Tyranny (complacent), emptiness (narcistic), or complaints (habitual).