November 2019

Monthly Archive

November 26, 2019

Posted by larvalsubjects under

Uncategorized

[6] Comments

In Speculative Grace, Adam Miller distinguishes science and religion on the basis of two sorts of vision. On the one hand, Miller says, science cultivates farsightedness. Perhaps we could say that science is the exploration of something like Morton’s hyperobjects or Deleuze and Bergson’s durations inferior and superior to our own. Science relates us to nearly unimaginable spaces and times at the level of the vastly small and the overwhelmingly large. In the theory of evolution we are linked to breathtaking scales of time, linking species and geographical processes that have unfolded over the course of millions and billions of years. Like the theory of evolution, astronomy and physics link us to sublime distances and ages we can barely conceive. We learn that it takes eight minutes for sunlight to reach us (compare this to our experience of the a room being illuminated when we flip a switch), or that it takes 230 million years for our sun to orbit the Milky Way, our how beings like our solar system are formed through a process of accretion out of the detritus of ancient stars that spread their matter throughout the universe in unimaginably violent supernovas. In quantum physics we learn of the strange probabilistic behavior of subatomic particles that are both waves and particles and that seem to violate the speed of light through phenomena of quantum entanglement. And, of course, environmental science reveals the vast and hyper-complex world of climate change and how our local actions are related to the the behavior of systems at scales incredibly difficult for us to think and conceptualize. If science is farsighted, then this is because it cultivates a relationship to distance at the smallest and largest scales of time and space, showing us how we are deeply enmeshed and entangled in these things that seem so remote from our day to day experience.

In Speculative Grace, Adam Miller distinguishes science and religion on the basis of two sorts of vision. On the one hand, Miller says, science cultivates farsightedness. Perhaps we could say that science is the exploration of something like Morton’s hyperobjects or Deleuze and Bergson’s durations inferior and superior to our own. Science relates us to nearly unimaginable spaces and times at the level of the vastly small and the overwhelmingly large. In the theory of evolution we are linked to breathtaking scales of time, linking species and geographical processes that have unfolded over the course of millions and billions of years. Like the theory of evolution, astronomy and physics link us to sublime distances and ages we can barely conceive. We learn that it takes eight minutes for sunlight to reach us (compare this to our experience of the a room being illuminated when we flip a switch), or that it takes 230 million years for our sun to orbit the Milky Way, our how beings like our solar system are formed through a process of accretion out of the detritus of ancient stars that spread their matter throughout the universe in unimaginably violent supernovas. In quantum physics we learn of the strange probabilistic behavior of subatomic particles that are both waves and particles and that seem to violate the speed of light through phenomena of quantum entanglement. And, of course, environmental science reveals the vast and hyper-complex world of climate change and how our local actions are related to the the behavior of systems at scales incredibly difficult for us to think and conceptualize. If science is farsighted, then this is because it cultivates a relationship to distance at the smallest and largest scales of time and space, showing us how we are deeply enmeshed and entangled in these things that seem so remote from our day to day experience.

Religion, according to Miller and by contrast, is about developing nearsightedness. Where science under his reading is about developing a relation to distance, religion is about developing proximity. As Miller puts it,

Religion corrects for our farsightedness. It addresses the invisibility of objects that are commonly too familiar, too available, too immanent to be seen. To this end, it intentionally cultivates nearsightedness. Religion practices myopia in order to bring both work and suffering into focus as grace. Redemption turns on this revelation. (Speculative Grace, 143)

I am not certain that I share Miller’s view that this is what is unique to religion, but conceptually I like what he is doing here. Within Miller’s framework, all of the ordinary concepts of Christianity are transformed. Ordinarily we think of religion, and Christianity in particular, as a yearning for transcendence that aims at something out of this world. Consider, for example, Hägglund’s critique of religion in his magnificent book, This Life. In Miller’s account, by contrast– and don’t worry readers, I haven’t suddenly become religious –religion centers us directly in this world and the things of this world. For Miller– and again I don’t think this need be unique to religion –religion aims not at transcendence, the beyond, a super-empirical world, but rather at immanence, this world, those things that are nearest to us.

Take the traditional concept of grace. According to the Wikipedia entry on grace in Christianity,

grace is “the love and mercy given to us by God because God desires us to have it, not necessarily because of anything we have done to earn it”. It is not a created substance of any kind. “Grace is favour, the free and undeserved help that God gives us to respond to his call to become children of God, adoptive sons, partakers of the divine nature and of eternal life.” It is understood by Christians to be a spontaneous gift from God to people “generous, free and totally unexpected and undeserved” – that takes the form of divine favor, love, clemency, and a share in the divine life of God.

Under this model, grace descends upon us from a verticality. We exist in a state of sin from which we cannot escape. Grace is the clemency that God grants us, the undeserved gift, that rescues us from this sin.

Nothing could be further from Miller’s concept of grace. Miller wants to do for the concept of grace, what Darwin did for our conception of species. Where pre-Darwinian accounts of species held that the world was not enough, but rather that species are created by God and are modeled after the ideas in his divine intellect, Darwin’s declaration under Miller’s reading, was that the world is enough. Darwin proceeded to show how we can give an account of the genesis of species from within the world without recourse to any transcendent supplements. Such is the theory of evolution. It is premised on immanence, rather than transcendence.

read on!

(more…)

November 20, 2019

Posted by larvalsubjects under

Uncategorized

[4] Comments

With horror I didn’t realize what had come out of my mouth until after I said it. Yesterday a student came up to me after class, breathlessly talking about how they just couldn’t understand how Miller’s experimental metaphysics and method could work. “Professor Bryant, I just don’t understand and I don’t know what my problem is?” What sections should I be focusing on to figure this out? Why am I having this problem understanding this?”

With horror I didn’t realize what had come out of my mouth until after I said it. Yesterday a student came up to me after class, breathlessly talking about how they just couldn’t understand how Miller’s experimental metaphysics and method could work. “Professor Bryant, I just don’t understand and I don’t know what my problem is?” What sections should I be focusing on to figure this out? Why am I having this problem understanding this?”

And then it happened. I said it before I realized what I was saying. “I think your problem is that you need more confidence!” This student has been with me for three semesters and they’re brilliant. Their eyes widened and fluttered with surprise. I continued. “Maybe the problem isn’t with you. Maybe it’s not that you’re failing to understand. Maybe you understand perfectly well what is in the book. Maybe the problem is with the book. Rather than this being a failure of your understanding, a deficiency on your part, maybe you’re doing philosophy now. Maybe you’re recognizing something that’s inadequate in the text, that isn’t satisfactory, that just doesn’t work and that something else is needed.” The student responded, “no, I just don’t think I understand.”

I don’t think there are enough moments like this in the classroom. There is a way of teaching that can be described as paranoid. There is an impulse in many of us to always be advocates of the texts we are teaching (and that’s not a bad thing!). When a student raises a question about a thinker or a text, when they express confusion, our impulse is to explain and show how the text and thinker has an answer. Often that’s the appropriate move as the student, after all, is just learning these texts and is only being exposed to a limited selection of the thinker’s work. This pedagogical approach can be paranoid in that it fills in the gaps and presents the author and text as if they are invincible. We teach as if, to quote Lacan, “the big Other exists”. The problem with proceeding in this way is that we are creating a certain subjectivity in our students. After years of this sort of training in philosophy, literature, and cultural studies courses the student becomes convinced that their questions are the result of a failure to understand, their own insufficiency, rather than an insufficiency of the text. We Oedipalize our subjects. In Lacan’s dialectic of alienation and separation, they remain at the level of alienation in the big Other, believing that the big Other is without antagonisms, lack, incompleteness, and insufficiency– Deleuze and Lacan can never be wrong, and certainly not Hegel! –and they are therefore never able to move on to separation so that they might become subjects themselves. Such is the lesson of Lacan’s university discourse. The product of that discourse is an alienated subject, a subject trapped in the web of “knowledge” and a master-signifier, whether it be a figure (Lacan, Hegel, Deleuze, Spinoza, Kant, etc.) that is treated as the repository of complete knowledge such that they can never be wrong. A non-paranoid pedagogy would refuse the move of treating the text and figure as if it is always right, as if any question posed to the text is the result of a failure to understand.

I don’t think there are enough moments like this in the classroom. There is a way of teaching that can be described as paranoid. There is an impulse in many of us to always be advocates of the texts we are teaching (and that’s not a bad thing!). When a student raises a question about a thinker or a text, when they express confusion, our impulse is to explain and show how the text and thinker has an answer. Often that’s the appropriate move as the student, after all, is just learning these texts and is only being exposed to a limited selection of the thinker’s work. This pedagogical approach can be paranoid in that it fills in the gaps and presents the author and text as if they are invincible. We teach as if, to quote Lacan, “the big Other exists”. The problem with proceeding in this way is that we are creating a certain subjectivity in our students. After years of this sort of training in philosophy, literature, and cultural studies courses the student becomes convinced that their questions are the result of a failure to understand, their own insufficiency, rather than an insufficiency of the text. We Oedipalize our subjects. In Lacan’s dialectic of alienation and separation, they remain at the level of alienation in the big Other, believing that the big Other is without antagonisms, lack, incompleteness, and insufficiency– Deleuze and Lacan can never be wrong, and certainly not Hegel! –and they are therefore never able to move on to separation so that they might become subjects themselves. Such is the lesson of Lacan’s university discourse. The product of that discourse is an alienated subject, a subject trapped in the web of “knowledge” and a master-signifier, whether it be a figure (Lacan, Hegel, Deleuze, Spinoza, Kant, etc.) that is treated as the repository of complete knowledge such that they can never be wrong. A non-paranoid pedagogy would refuse the move of treating the text and figure as if it is always right, as if any question posed to the text is the result of a failure to understand.

November 19, 2019

Posted by larvalsubjects under

Uncategorized

[2] Comments

In place of the conspiracy theories of classical metaphysics, Adam Miller, following Latour, proposes an experimental metaphysics. According to Miller, what is the cardinal sin of classical metaphysics? On the one hand, it is reductive. When we are in the grips of a theory, we believe we have mastered the phenomena. Our metaphysics is based on a distinction between appearance and reality, where appearances are the buzzing confusion of all things that exist in the world and reality is the finite set of principles or laws that both explain those phenomena and that are the grounds of the phenomena. Here I cannot resist a hackneyed reference to The Matrix. What is it that distinguishes Neo from everyone else? Unlike the rest of us that see only appearances– the steak that we are eating, the clothing we are wearing, the car we’re driving in, other people, etc –Neo sees the reality that governs the appearances. He sees the code that governs appearances. Neo is the Platonic hero par excellence. Where everyone else sees shadows on the cave wall taking them to be true reality, Neo has escaped the cave, seen the true reality, and now knows the combinatorial laws that govern all the appearances. It is this that allows him to perform such extraordinary feats, for like the scientist that has unlocked the secrets of nature, he can manipulate that code to his advantage.

In place of the conspiracy theories of classical metaphysics, Adam Miller, following Latour, proposes an experimental metaphysics. According to Miller, what is the cardinal sin of classical metaphysics? On the one hand, it is reductive. When we are in the grips of a theory, we believe we have mastered the phenomena. Our metaphysics is based on a distinction between appearance and reality, where appearances are the buzzing confusion of all things that exist in the world and reality is the finite set of principles or laws that both explain those phenomena and that are the grounds of the phenomena. Here I cannot resist a hackneyed reference to The Matrix. What is it that distinguishes Neo from everyone else? Unlike the rest of us that see only appearances– the steak that we are eating, the clothing we are wearing, the car we’re driving in, other people, etc –Neo sees the reality that governs the appearances. He sees the code that governs appearances. Neo is the Platonic hero par excellence. Where everyone else sees shadows on the cave wall taking them to be true reality, Neo has escaped the cave, seen the true reality, and now knows the combinatorial laws that govern all the appearances. It is this that allows him to perform such extraordinary feats, for like the scientist that has unlocked the secrets of nature, he can manipulate that code to his advantage.

This is the fantasy of classical metaphysics and is what Miller refers to as a conspiracy theory. The classical metaphysician believes he has unliked the code that governs the appearances and, for this reason, no longer has to attend to the appearances. Alfred Korzybski famously said “the map is not the territory”. The classical metaphysician is like a person who gets a map and thinks that because they have a map they have mastered the territory; so much so that they don’t have to consult the territory at all. In this instance, the map, the model, comes to replace the territory altogether. The map becomes the reality and the territory itself, such that the territory no longer enters the picture. Perhaps this is one of the reasons people often find philosophers so frustrating. We have our models, we have our metaphysics, and we debate back and forth about the finer points of these respective maps, yet the territory doesn’t enter the picture. The map has become more real than the territory (isn’t this what Lauruelle is diagnosing in his non-philosophy: the manner in which the philosophy posits its own reality).

This is the fantasy of classical metaphysics and is what Miller refers to as a conspiracy theory. The classical metaphysician believes he has unliked the code that governs the appearances and, for this reason, no longer has to attend to the appearances. Alfred Korzybski famously said “the map is not the territory”. The classical metaphysician is like a person who gets a map and thinks that because they have a map they have mastered the territory; so much so that they don’t have to consult the territory at all. In this instance, the map, the model, comes to replace the territory altogether. The map becomes the reality and the territory itself, such that the territory no longer enters the picture. Perhaps this is one of the reasons people often find philosophers so frustrating. We have our models, we have our metaphysics, and we debate back and forth about the finer points of these respective maps, yet the territory doesn’t enter the picture. The map has become more real than the territory (isn’t this what Lauruelle is diagnosing in his non-philosophy: the manner in which the philosophy posits its own reality).

It is in this sense that classical metaphysics is reductive: the map comes to replace the territory such that the territory contributes nothing. Indeed, the territory comes to be treated as an epiphenomenon. Consider the following equations:

appearances/reality

lemon/combinations of atoms

The latter might be an equation from Lucretian atomism. That thesis states that the lemon is explained by combinations of atoms, both the shapes of those atoms and how they are combined. Now, in the Lucretian framework– as much as it pains me to say so, given my deep love of Lucretius –we can ask whether the lemon contributes anything? Isn’t it the atoms that do all of the work? Suppose we take a neo-atomist. Someone says it was the baseball that broke the window. Our neo-atomist smugly responds that that is a folk metaphysical explanation. Rather, what really happened is that one combination of atoms interacted with another set of atoms producing a new combination of atoms. Baseballs and windows contribute nothing. They are fictions.

read on!

(more…)

November 18, 2019

Posted by larvalsubjects under

Uncategorized

1 Comment

In In Defense of Things Bjørnar Olsen reminds us that the etymology of the term “thing” is instructive. As articulated by The Online Etymology Dictionary,

In In Defense of Things Bjørnar Olsen reminds us that the etymology of the term “thing” is instructive. As articulated by The Online Etymology Dictionary,

Old English þing “meeting, assembly, council, discussion,” later “entity, being, matter” (subject of deliberation in an assembly), also “act, deed, event, material object, body, being, creature,” from Proto-Germanic *thinga- “assembly” (source also of Old Frisian thing “assembly, council, suit, matter, thing,” Middle Dutch dinc “court-day, suit, plea, concern, affair, thing,” Dutch ding “thing,” Old High German ding “public assembly for judgment and business, lawsuit,” German Ding “affair, matter, thing,” Old Norse þing “public assembly”). The Germanic word is perhaps literally “appointed time,” from a PIE *tenk- (1), from root *ten- “stretch,” perhaps on notion of “stretch of time for a meeting or assembly.”

How do we get from þing as meeting, assembly, council, or discussion to the idea of a thing as an entity? What is the chain of associations here? As Harman will say in Guerrilla Metaphysics, “we have a universe made up of objects wrapped in objects wrapped in objects wrapped in objects”, as “every object is both a substance and a complex of relations” (83). A thing is an assembly, a meeting of things, a complex of things. When confronted with Kant’s second antinomy and the choice between the thesis:

Every composite substance in the world is made up of simple parts, and nothing anywhere exists save the simple or what is composed of the simple.

And the anti-thesis:

No composite thing in the world is made up of simple parts, and nowhere exists in the world anything simple.

Object-oriented ontology resolutely sides with the anti-thesis. It begins with the speculative thesis that there are no simple or atomic units. While I do not share Graham’s antipathy towards materialism insofar as I don’t think this must be the commitment of materialism, I think this commitment is at the heart of his hostility to materialisms. If I’ve understand Harman correctly, he sees materialism as committed to the thesis of Kant’s second antinomy. It is committed to the thesis that there are ultimate units, simple parts, that are the ultimate constituents of being.

read on!

(more…)

November 18, 2019

Posted by larvalsubjects under

Uncategorized

1 Comment

Recently I’ve been thinking a lot about old zoos and their significance. It is my view that all of our comportments towards the world and all of our action presuppose a pre-reflective ontological understanding of being. To say that it is pre-reflective is to say that it is operative in our thought, understanding, and action without us being aware of it. It is the lens through which we encounter and act upon beings. However, it is a strange sort of lens, for it is unconscious and therefore engenders the sense that this is just how it is with the beings themselves, rather than being the lens through which we encounter beings. Often our pre-reflective ontologies are deeply inconsistent and cause us all sorts of problems which we are unable to recognize because we don’t recognize the way in which they arise from our own lenses. A philosophical ontology, by contrast, attempts to render our pre-reflective ontologies explicit and subject them to critique.

Recently I’ve been thinking a lot about old zoos and their significance. It is my view that all of our comportments towards the world and all of our action presuppose a pre-reflective ontological understanding of being. To say that it is pre-reflective is to say that it is operative in our thought, understanding, and action without us being aware of it. It is the lens through which we encounter and act upon beings. However, it is a strange sort of lens, for it is unconscious and therefore engenders the sense that this is just how it is with the beings themselves, rather than being the lens through which we encounter beings. Often our pre-reflective ontologies are deeply inconsistent and cause us all sorts of problems which we are unable to recognize because we don’t recognize the way in which they arise from our own lenses. A philosophical ontology, by contrast, attempts to render our pre-reflective ontologies explicit and subject them to critique.

So, with this in mind, back to the old zoos. We can approach the way people represent things, the things they build, and the way they pose problems as symptoms of their pre-reflective ontologies. Just as a very simple dream can be a symptom of a highly complex thought uncovered through the process of free association, a human representation or artifact can be seen as a symptom of a broader set of ontological assumptions or assumptions about the nature of being. In the old zoos we encounter the animal caged, behind bars, with little to nothing in their cell. How must one think of beings– not just animals –to construct a zoo such as this? Is there a more generalized set of ontological assumptions reflected in this zoo construction?

So, with this in mind, back to the old zoos. We can approach the way people represent things, the things they build, and the way they pose problems as symptoms of their pre-reflective ontologies. Just as a very simple dream can be a symptom of a highly complex thought uncovered through the process of free association, a human representation or artifact can be seen as a symptom of a broader set of ontological assumptions or assumptions about the nature of being. In the old zoos we encounter the animal caged, behind bars, with little to nothing in their cell. How must one think of beings– not just animals –to construct a zoo such as this? Is there a more generalized set of ontological assumptions reflected in this zoo construction?

The leopard or zebra in a cell such as this is quite literally an abstraction. These animals have been reduced to abstractions. Throughout his work, Husserl regularly points out that the objects of our intentions are structured around internal and external horizons. The marker sitting on my desk presents itself to me in profiles. I am never able to apprehend all of the marker at once. I pick it up and I turn it about, and now new profiles appear or give themselves. The others disappear. I intend or apprehend the marker as a unity, as a totality, but it is never given all at once. Elements of it are present and others are absent. Nonetheless, it is given to me as a whole or a totality. The absent profiles I intend in the marker are the internal horizon of the marker. This internal horizon is deeply temporal as well. I anticipate the profiles that will appear should I turn the marker about, and I retend the profiles that disappeared as I make new profiles appear. Indeed, the very act of grasping the marker despite the fact that profiles of it are absent in my visual perception of it already indicate the work of a bodily intentionality in my engagement with things that encounters them as unities and totalities, rather than two-dimensional beings gradually built up out of atomic sensations.

The leopard or zebra in a cell such as this is quite literally an abstraction. These animals have been reduced to abstractions. Throughout his work, Husserl regularly points out that the objects of our intentions are structured around internal and external horizons. The marker sitting on my desk presents itself to me in profiles. I am never able to apprehend all of the marker at once. I pick it up and I turn it about, and now new profiles appear or give themselves. The others disappear. I intend or apprehend the marker as a unity, as a totality, but it is never given all at once. Elements of it are present and others are absent. Nonetheless, it is given to me as a whole or a totality. The absent profiles I intend in the marker are the internal horizon of the marker. This internal horizon is deeply temporal as well. I anticipate the profiles that will appear should I turn the marker about, and I retend the profiles that disappeared as I make new profiles appear. Indeed, the very act of grasping the marker despite the fact that profiles of it are absent in my visual perception of it already indicate the work of a bodily intentionality in my engagement with things that encounters them as unities and totalities, rather than two-dimensional beings gradually built up out of atomic sensations.

read on!

(more…)

November 16, 2019

Posted by larvalsubjects under

Uncategorized

[2] Comments

A few weeks ago I was teaching Epicurus and Lucretius in my Intro class. A moment from those lectures that occurred in all five of my sections has stuck with me ever since. After working through the basics of Epicurean ethics and how to live in such a way as to achieve, to the greatest degree possible, aponia we arrived at the problem of anxiety and the primary causes of our anxiety according to Epicurus and Lucretius. Within the Epicurean tradition, the first of these is superstition or religion (I don’t think the latter translation is the best insofar as religion doesn’t really become a distinct concept in Europe until the 17th century), while the second is fear of death; both the pain of dying and fear of punishment in the afterlife. Both of these, of course, are interrelated.

A few weeks ago I was teaching Epicurus and Lucretius in my Intro class. A moment from those lectures that occurred in all five of my sections has stuck with me ever since. After working through the basics of Epicurean ethics and how to live in such a way as to achieve, to the greatest degree possible, aponia we arrived at the problem of anxiety and the primary causes of our anxiety according to Epicurus and Lucretius. Within the Epicurean tradition, the first of these is superstition or religion (I don’t think the latter translation is the best insofar as religion doesn’t really become a distinct concept in Europe until the 17th century), while the second is fear of death; both the pain of dying and fear of punishment in the afterlife. Both of these, of course, are interrelated.

The Epicurean cure to the fear produced by superstition is the study of nature… A cure that I don’t think has been particularly effective because we know more about nature than at any other time, yet are as anxious as ever, perhaps even moreso. At any rate, I asked my students– again in five classes –what might be some reasons for studying nature and was startled by their answers. In each class they gave answers that indicated that they associated the signifier “nature” with the green, the biological, the living, and the animate. In other words, for my students, nature is green.

The Epicurean cure to the fear produced by superstition is the study of nature… A cure that I don’t think has been particularly effective because we know more about nature than at any other time, yet are as anxious as ever, perhaps even moreso. At any rate, I asked my students– again in five classes –what might be some reasons for studying nature and was startled by their answers. In each class they gave answers that indicated that they associated the signifier “nature” with the green, the biological, the living, and the animate. In other words, for my students, nature is green.

I think moments like this in the classroom are both important and powerful. I had a similar moment earlier in the semester when I asked my students at the beginning of the semester, in all six classes, whether the sentence “the kitchen is a political space” is a statement that makes sense to them. They were baffled by this enunciation, and in that moment I encountered something like a “gravitational anomaly” in Star Trek indicating the presence of something in space not visible to the naked eye. A moment like this indicates that each time I use the word “politics” in my classroom there is a lens through which they are hearing my words that is invisible to me. In the case of the signifier “nature” and its widespread association to all that is animate, biological, living, and green– a venerable conception of nature going all the way back to Aristotle and the title of his famous book, Physics –nature, for them, is what blooms, grows, moves, and perceives. However, this also entails that the rock, dirt, water, and the rest– all that is “inanimate” –is something other than “nature”. The surface of Mars or Jupiter is not, within this conceptual framework, nature. Insofar as the concepts we have inform our action, I believe this is a matter of deep concern, for, as the articles in Cohen’s Prismatic Ecologies argue, we must think ecology beyond green if we are to truly think ecologically. This I believe is the work of philosophy and art. We contribute, if only in a small way, to shifting conceptual assemblages in new and different directions helping in some small way to generate different ways of perceiving, acting, and living together. Our activism is both a poetic and conceptual work that helps to bring something of the buzzing confusion of being into relief.

I think moments like this in the classroom are both important and powerful. I had a similar moment earlier in the semester when I asked my students at the beginning of the semester, in all six classes, whether the sentence “the kitchen is a political space” is a statement that makes sense to them. They were baffled by this enunciation, and in that moment I encountered something like a “gravitational anomaly” in Star Trek indicating the presence of something in space not visible to the naked eye. A moment like this indicates that each time I use the word “politics” in my classroom there is a lens through which they are hearing my words that is invisible to me. In the case of the signifier “nature” and its widespread association to all that is animate, biological, living, and green– a venerable conception of nature going all the way back to Aristotle and the title of his famous book, Physics –nature, for them, is what blooms, grows, moves, and perceives. However, this also entails that the rock, dirt, water, and the rest– all that is “inanimate” –is something other than “nature”. The surface of Mars or Jupiter is not, within this conceptual framework, nature. Insofar as the concepts we have inform our action, I believe this is a matter of deep concern, for, as the articles in Cohen’s Prismatic Ecologies argue, we must think ecology beyond green if we are to truly think ecologically. This I believe is the work of philosophy and art. We contribute, if only in a small way, to shifting conceptual assemblages in new and different directions helping in some small way to generate different ways of perceiving, acting, and living together. Our activism is both a poetic and conceptual work that helps to bring something of the buzzing confusion of being into relief.

November 15, 2019

Posted by larvalsubjects under

Uncategorized

[2] Comments

This week I began teaching Adam Miller’s extraordinary and beautiful book Speculative Grace: Bruno Latour and Object-Oriented Theology for my Philosophy of Religion course. This is the third time I’ve read this surprising book, and I still find it deeply challenging both in the sense that it is difficult to pin down (I’m not sure what I was thinking by assigning it!) and in the sense that it provokes me to think deeper and harder. Composed of 41 short, sometimes cryptic, and terse chapters, Miller’s book is difficult to summarize. In many respects, I think, the book enacts one of its central claims. Things, objects, Miller says are “resistantly available”. This is his gloss on Latour’s thesis of irreduction: the real, Latour declares, is that which resists. While the thing enters into relations with other things in all sorts of ways, there is always something of the thing that resists its relations or that is irreducible to them. This is how it is with his book. There are lightning flashes of insight that render something of the book available, where relations are composed between the reader and the text, yet in its short, abbreviated formulations where examples are almost entirely absent, there is something of the book that always feels withdrawn or resistant. In this regard, the text is not only about the nature of things– in part; it is also about grace –but it also presents itself as a real thing of the universe or a force, no matter how humble. His book performs what it argues. Having known Adam now for fourteen years, this is how he himself is. He is a very quiet and dignified person, animated by a humble charisma, who discloses elements of himself in mysterious flashes, yet who you’re never quite sure you really know. He’s a singularity.

This week I began teaching Adam Miller’s extraordinary and beautiful book Speculative Grace: Bruno Latour and Object-Oriented Theology for my Philosophy of Religion course. This is the third time I’ve read this surprising book, and I still find it deeply challenging both in the sense that it is difficult to pin down (I’m not sure what I was thinking by assigning it!) and in the sense that it provokes me to think deeper and harder. Composed of 41 short, sometimes cryptic, and terse chapters, Miller’s book is difficult to summarize. In many respects, I think, the book enacts one of its central claims. Things, objects, Miller says are “resistantly available”. This is his gloss on Latour’s thesis of irreduction: the real, Latour declares, is that which resists. While the thing enters into relations with other things in all sorts of ways, there is always something of the thing that resists its relations or that is irreducible to them. This is how it is with his book. There are lightning flashes of insight that render something of the book available, where relations are composed between the reader and the text, yet in its short, abbreviated formulations where examples are almost entirely absent, there is something of the book that always feels withdrawn or resistant. In this regard, the text is not only about the nature of things– in part; it is also about grace –but it also presents itself as a real thing of the universe or a force, no matter how humble. His book performs what it argues. Having known Adam now for fourteen years, this is how he himself is. He is a very quiet and dignified person, animated by a humble charisma, who discloses elements of himself in mysterious flashes, yet who you’re never quite sure you really know. He’s a singularity.

In a vain attempt to introduce this potent and difficult concept, I brought up a picture of Edvard Munch’s famous painting at the end of class. I asked them to imagine the ideal book on this painting. Such a book would adopt every conceivable theoretical approach in producing a commentary. It would be biographical, historical, psychoanalytic, phenomenological, Marxist, deconstructive, feminist, eco-critical, etc. It would delve into the psychology of color and shape. We can. imagine a massive book written on a single painting. I asked them to imagine such a book and I left them with this question: could that ideal, comprehensive book replace the painting? Like Frank Jackson’s famous article “What Mary Didn’t Know”– though with a different aim in mind; it’s odd that he takes this as an argument against physicalism –I was asking them whether there was something of the painting that is irreducible to commentary. In a way, this is partially what Harman is getting at with his concept of withdrawal. There is something that resists, something that is irreducible, something that is withdrawn.

In the fourth chapter of the book, Miller makes the claim that classical metaphysics is overwhelmingly composed of conspiracy theories. One of his aims is to establish a form of metaphysical thinking that doesn’t fall into this trap. As he puts it,

Classically, metaphysicians consistently fall prey to the same temptation: they are conspiracy theorists. They assume a much higher degree of fundamental unity and intentional coordination than is actually needed to account for the patterned complexity of what is given. (SG, 9)

He begins the book already hinting at this thesis, discussing the difference between pre- and post-darwinian ways of thinking. In pre-darwinian models of thought, species are conceived as already formatted or modeled in the mind of God. Echoing Deleuze’s distinction between the difference between the possible and the real and the virtual and the actual, the possible is conceived as identical to the real, as a model that already exists, and the real is merely a passage from the possible into the actual that adds nothing of its own. The declaration of post-darwinian thought, says Miller, is that “the world is enough!” Rather than appealing to a verticality in the form of an omnipotent God that brings all species into being from his pre-existent concepts, the post-darwinian thinker instead resolves to account for the genesis of species within the world itself. Miller wishes to do the same thing with grace. Rather than seeing grace as dispensed from God on high, he wants to instead develop an immanent account of grace arising from out of the buzzing and chaotic mesh of the world.

Miller continues,

As a venerable brand of ivory tower conspiracy theory, the very work of metaphysics has long been understood as the task of unveiling some invisible hand at work behind the scenes, directing and unifying the movements of the disorganized and passive multitude into a coherent whole by unilaterally reducing that multitude to some more basic common factor. This shadow hole assigned to this basic common factor can just as easily be played by God, Platonic forms, or Kantian categories as by semiotic systems, capitalism, or subatomic particles. There is– ingrained in the metaphysical disposition itself –a drive for purity, and this purity is produced by requiring all phenomena to be baptized in the cleansing waters of reductionism. (SG, 9 – 10)

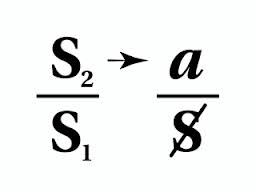

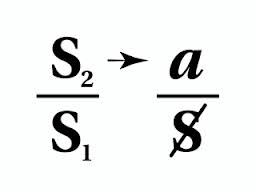

What Miller describes here, I think, is aptly formalized by the lefthand side of Lacan’s graph of sexuation. The upper portion of the equation can be read as saying “there exists a being that is the unconditioned ground of all else”, while the lower portion of the equation can be read as saying “all beings are grounded in, conditioned by, and accounted for by the agency of this being. This is a formalization of the logic of sovereignty in all its forms, or, as Miller calls them, conspiracy theories.

What Miller describes here, I think, is aptly formalized by the lefthand side of Lacan’s graph of sexuation. The upper portion of the equation can be read as saying “there exists a being that is the unconditioned ground of all else”, while the lower portion of the equation can be read as saying “all beings are grounded in, conditioned by, and accounted for by the agency of this being. This is a formalization of the logic of sovereignty in all its forms, or, as Miller calls them, conspiracy theories.

read on!

(more…)

November 13, 2019

Posted by larvalsubjects under

Uncategorized

1 Comment

Over at synthetic zero, Michael James has a lovely post on feral philosophy. We’ve never been enemies, by the way. Check it out here.

In Speculative Grace, Adam Miller distinguishes science and religion on the basis of two sorts of vision. On the one hand, Miller says, science cultivates farsightedness. Perhaps we could say that science is the exploration of something like Morton’s hyperobjects or Deleuze and Bergson’s durations inferior and superior to our own. Science relates us to nearly unimaginable spaces and times at the level of the vastly small and the overwhelmingly large. In the theory of evolution we are linked to breathtaking scales of time, linking species and geographical processes that have unfolded over the course of millions and billions of years. Like the theory of evolution, astronomy and physics link us to sublime distances and ages we can barely conceive. We learn that it takes eight minutes for sunlight to reach us (compare this to our experience of the a room being illuminated when we flip a switch), or that it takes 230 million years for our sun to orbit the Milky Way, our how beings like our solar system are formed through a process of accretion out of the detritus of ancient stars that spread their matter throughout the universe in unimaginably violent supernovas. In quantum physics we learn of the strange probabilistic behavior of subatomic particles that are both waves and particles and that seem to violate the speed of light through phenomena of quantum entanglement. And, of course, environmental science reveals the vast and hyper-complex world of climate change and how our local actions are related to the the behavior of systems at scales incredibly difficult for us to think and conceptualize. If science is farsighted, then this is because it cultivates a relationship to distance at the smallest and largest scales of time and space, showing us how we are deeply enmeshed and entangled in these things that seem so remote from our day to day experience.

In Speculative Grace, Adam Miller distinguishes science and religion on the basis of two sorts of vision. On the one hand, Miller says, science cultivates farsightedness. Perhaps we could say that science is the exploration of something like Morton’s hyperobjects or Deleuze and Bergson’s durations inferior and superior to our own. Science relates us to nearly unimaginable spaces and times at the level of the vastly small and the overwhelmingly large. In the theory of evolution we are linked to breathtaking scales of time, linking species and geographical processes that have unfolded over the course of millions and billions of years. Like the theory of evolution, astronomy and physics link us to sublime distances and ages we can barely conceive. We learn that it takes eight minutes for sunlight to reach us (compare this to our experience of the a room being illuminated when we flip a switch), or that it takes 230 million years for our sun to orbit the Milky Way, our how beings like our solar system are formed through a process of accretion out of the detritus of ancient stars that spread their matter throughout the universe in unimaginably violent supernovas. In quantum physics we learn of the strange probabilistic behavior of subatomic particles that are both waves and particles and that seem to violate the speed of light through phenomena of quantum entanglement. And, of course, environmental science reveals the vast and hyper-complex world of climate change and how our local actions are related to the the behavior of systems at scales incredibly difficult for us to think and conceptualize. If science is farsighted, then this is because it cultivates a relationship to distance at the smallest and largest scales of time and space, showing us how we are deeply enmeshed and entangled in these things that seem so remote from our day to day experience. With horror I didn’t realize what had come out of my mouth until after I said it. Yesterday a student came up to me after class, breathlessly talking about how they just couldn’t understand how Miller’s experimental metaphysics and method could work. “Professor Bryant, I just don’t understand and I don’t know what my problem is?” What sections should I be focusing on to figure this out? Why am I having this problem understanding this?”

With horror I didn’t realize what had come out of my mouth until after I said it. Yesterday a student came up to me after class, breathlessly talking about how they just couldn’t understand how Miller’s experimental metaphysics and method could work. “Professor Bryant, I just don’t understand and I don’t know what my problem is?” What sections should I be focusing on to figure this out? Why am I having this problem understanding this?” I don’t think there are enough moments like this in the classroom. There is a way of teaching that can be described as paranoid. There is an impulse in many of us to always be advocates of the texts we are teaching (and that’s not a bad thing!). When a student raises a question about a thinker or a text, when they express confusion, our impulse is to explain and show how the text and thinker has an answer. Often that’s the appropriate move as the student, after all, is just learning these texts and is only being exposed to a limited selection of the thinker’s work. This pedagogical approach can be paranoid in that it fills in the gaps and presents the author and text as if they are invincible. We teach as if, to quote Lacan, “the big Other exists”. The problem with proceeding in this way is that we are creating a certain subjectivity in our students. After years of this sort of training in philosophy, literature, and cultural studies courses the student becomes convinced that their questions are the result of a failure to understand, their own insufficiency, rather than an insufficiency of the text. We Oedipalize our subjects. In Lacan’s dialectic of alienation and separation, they remain at the level of alienation in the big Other, believing that the big Other is without antagonisms, lack, incompleteness, and insufficiency– Deleuze and Lacan can never be wrong, and certainly not Hegel! –and they are therefore never able to move on to separation so that they might become subjects themselves. Such is the lesson of Lacan’s university discourse. The product of that discourse is an alienated subject, a subject trapped in the web of “knowledge” and a master-signifier, whether it be a figure (Lacan, Hegel, Deleuze, Spinoza, Kant, etc.) that is treated as the repository of complete knowledge such that they can never be wrong. A non-paranoid pedagogy would refuse the move of treating the text and figure as if it is always right, as if any question posed to the text is the result of a failure to understand.

I don’t think there are enough moments like this in the classroom. There is a way of teaching that can be described as paranoid. There is an impulse in many of us to always be advocates of the texts we are teaching (and that’s not a bad thing!). When a student raises a question about a thinker or a text, when they express confusion, our impulse is to explain and show how the text and thinker has an answer. Often that’s the appropriate move as the student, after all, is just learning these texts and is only being exposed to a limited selection of the thinker’s work. This pedagogical approach can be paranoid in that it fills in the gaps and presents the author and text as if they are invincible. We teach as if, to quote Lacan, “the big Other exists”. The problem with proceeding in this way is that we are creating a certain subjectivity in our students. After years of this sort of training in philosophy, literature, and cultural studies courses the student becomes convinced that their questions are the result of a failure to understand, their own insufficiency, rather than an insufficiency of the text. We Oedipalize our subjects. In Lacan’s dialectic of alienation and separation, they remain at the level of alienation in the big Other, believing that the big Other is without antagonisms, lack, incompleteness, and insufficiency– Deleuze and Lacan can never be wrong, and certainly not Hegel! –and they are therefore never able to move on to separation so that they might become subjects themselves. Such is the lesson of Lacan’s university discourse. The product of that discourse is an alienated subject, a subject trapped in the web of “knowledge” and a master-signifier, whether it be a figure (Lacan, Hegel, Deleuze, Spinoza, Kant, etc.) that is treated as the repository of complete knowledge such that they can never be wrong. A non-paranoid pedagogy would refuse the move of treating the text and figure as if it is always right, as if any question posed to the text is the result of a failure to understand. In place of the

In place of the  This is the fantasy of classical metaphysics and is what Miller refers to as a conspiracy theory. The classical metaphysician believes he has unliked the code that governs the appearances and, for this reason, no longer has to attend to the appearances. Alfred Korzybski famously said “the map is not the territory”. The classical metaphysician is like a person who gets a map and thinks that because they have a map they have mastered the territory; so much so that they don’t have to consult the territory at all. In this instance, the map, the model, comes to replace the territory altogether. The map becomes the reality and the territory itself, such that the territory no longer enters the picture. Perhaps this is one of the reasons people often find philosophers so frustrating. We have our models, we have our metaphysics, and we debate back and forth about the finer points of these respective maps, yet the territory doesn’t enter the picture. The map has become more real than the territory (isn’t this what Lauruelle is diagnosing in his non-philosophy: the manner in which the philosophy posits its own reality).

This is the fantasy of classical metaphysics and is what Miller refers to as a conspiracy theory. The classical metaphysician believes he has unliked the code that governs the appearances and, for this reason, no longer has to attend to the appearances. Alfred Korzybski famously said “the map is not the territory”. The classical metaphysician is like a person who gets a map and thinks that because they have a map they have mastered the territory; so much so that they don’t have to consult the territory at all. In this instance, the map, the model, comes to replace the territory altogether. The map becomes the reality and the territory itself, such that the territory no longer enters the picture. Perhaps this is one of the reasons people often find philosophers so frustrating. We have our models, we have our metaphysics, and we debate back and forth about the finer points of these respective maps, yet the territory doesn’t enter the picture. The map has become more real than the territory (isn’t this what Lauruelle is diagnosing in his non-philosophy: the manner in which the philosophy posits its own reality). In In Defense of Things Bjørnar Olsen reminds us that the etymology of the term “thing” is instructive. As articulated by

In In Defense of Things Bjørnar Olsen reminds us that the etymology of the term “thing” is instructive. As articulated by  Recently I’ve been thinking a lot about old zoos and their significance. It is my view that all of our comportments towards the world and all of our action presuppose a pre-reflective ontological understanding of being. To say that it is pre-reflective is to say that it is operative in our thought, understanding, and action without us being aware of it. It is the lens through which we encounter and act upon beings. However, it is a strange sort of lens, for it is unconscious and therefore engenders the sense that this is just how it is with the beings themselves, rather than being the lens through which we encounter beings. Often our pre-reflective ontologies are deeply inconsistent and cause us all sorts of problems which we are unable to recognize because we don’t recognize the way in which they arise from our own lenses. A philosophical ontology, by contrast, attempts to render our pre-reflective ontologies explicit and subject them to critique.

Recently I’ve been thinking a lot about old zoos and their significance. It is my view that all of our comportments towards the world and all of our action presuppose a pre-reflective ontological understanding of being. To say that it is pre-reflective is to say that it is operative in our thought, understanding, and action without us being aware of it. It is the lens through which we encounter and act upon beings. However, it is a strange sort of lens, for it is unconscious and therefore engenders the sense that this is just how it is with the beings themselves, rather than being the lens through which we encounter beings. Often our pre-reflective ontologies are deeply inconsistent and cause us all sorts of problems which we are unable to recognize because we don’t recognize the way in which they arise from our own lenses. A philosophical ontology, by contrast, attempts to render our pre-reflective ontologies explicit and subject them to critique. So, with this in mind, back to the old zoos. We can approach the way people represent things, the things they build, and the way they pose problems as symptoms of their pre-reflective ontologies. Just as a very simple dream can be a symptom of a highly complex thought uncovered through the process of free association, a human representation or artifact can be seen as a symptom of a broader set of ontological assumptions or assumptions about the nature of being. In the old zoos we encounter the animal caged, behind bars, with little to nothing in their cell. How must one think of beings– not just animals –to construct a zoo such as this? Is there a more generalized set of ontological assumptions reflected in this zoo construction?

So, with this in mind, back to the old zoos. We can approach the way people represent things, the things they build, and the way they pose problems as symptoms of their pre-reflective ontologies. Just as a very simple dream can be a symptom of a highly complex thought uncovered through the process of free association, a human representation or artifact can be seen as a symptom of a broader set of ontological assumptions or assumptions about the nature of being. In the old zoos we encounter the animal caged, behind bars, with little to nothing in their cell. How must one think of beings– not just animals –to construct a zoo such as this? Is there a more generalized set of ontological assumptions reflected in this zoo construction? The leopard or zebra in a cell such as this is quite literally an abstraction. These animals have been reduced to abstractions. Throughout his work, Husserl regularly points out that the objects of our intentions are structured around internal and external horizons. The marker sitting on my desk presents itself to me in profiles. I am never able to apprehend all of the marker at once. I pick it up and I turn it about, and now new profiles appear or give themselves. The others disappear. I intend or apprehend the marker as a unity, as a totality, but it is never given all at once. Elements of it are present and others are absent. Nonetheless, it is given to me as a whole or a totality. The absent profiles I intend in the marker are the internal horizon of the marker. This internal horizon is deeply temporal as well. I anticipate the profiles that will appear should I turn the marker about, and I retend the profiles that disappeared as I make new profiles appear. Indeed, the very act of grasping the marker despite the fact that profiles of it are absent in my visual perception of it already indicate the work of a bodily intentionality in my engagement with things that encounters them as unities and totalities, rather than two-dimensional beings gradually built up out of atomic sensations.

The leopard or zebra in a cell such as this is quite literally an abstraction. These animals have been reduced to abstractions. Throughout his work, Husserl regularly points out that the objects of our intentions are structured around internal and external horizons. The marker sitting on my desk presents itself to me in profiles. I am never able to apprehend all of the marker at once. I pick it up and I turn it about, and now new profiles appear or give themselves. The others disappear. I intend or apprehend the marker as a unity, as a totality, but it is never given all at once. Elements of it are present and others are absent. Nonetheless, it is given to me as a whole or a totality. The absent profiles I intend in the marker are the internal horizon of the marker. This internal horizon is deeply temporal as well. I anticipate the profiles that will appear should I turn the marker about, and I retend the profiles that disappeared as I make new profiles appear. Indeed, the very act of grasping the marker despite the fact that profiles of it are absent in my visual perception of it already indicate the work of a bodily intentionality in my engagement with things that encounters them as unities and totalities, rather than two-dimensional beings gradually built up out of atomic sensations. A few weeks ago I was teaching Epicurus and Lucretius in my Intro class. A moment from those lectures that occurred in all five of my sections has stuck with me ever since. After working through the basics of Epicurean ethics and how to live in such a way as to achieve, to the greatest degree possible, aponia we arrived at the problem of anxiety and the primary causes of our anxiety according to Epicurus and Lucretius. Within the Epicurean tradition, the first of these is superstition or religion (I don’t think the latter translation is the best insofar as religion doesn’t really become a distinct concept in Europe until the 17th century), while the second is fear of death; both the pain of dying and fear of punishment in the afterlife. Both of these, of course, are interrelated.

A few weeks ago I was teaching Epicurus and Lucretius in my Intro class. A moment from those lectures that occurred in all five of my sections has stuck with me ever since. After working through the basics of Epicurean ethics and how to live in such a way as to achieve, to the greatest degree possible, aponia we arrived at the problem of anxiety and the primary causes of our anxiety according to Epicurus and Lucretius. Within the Epicurean tradition, the first of these is superstition or religion (I don’t think the latter translation is the best insofar as religion doesn’t really become a distinct concept in Europe until the 17th century), while the second is fear of death; both the pain of dying and fear of punishment in the afterlife. Both of these, of course, are interrelated. The Epicurean cure to the fear produced by superstition is the study of nature… A cure that I don’t think has been particularly effective because we know more about nature than at any other time, yet are as anxious as ever, perhaps even moreso. At any rate, I asked my students– again in five classes –what might be some reasons for studying nature and was startled by their answers. In each class they gave answers that indicated that they associated the signifier “nature” with the green, the biological, the living, and the animate. In other words, for my students, nature is green.

The Epicurean cure to the fear produced by superstition is the study of nature… A cure that I don’t think has been particularly effective because we know more about nature than at any other time, yet are as anxious as ever, perhaps even moreso. At any rate, I asked my students– again in five classes –what might be some reasons for studying nature and was startled by their answers. In each class they gave answers that indicated that they associated the signifier “nature” with the green, the biological, the living, and the animate. In other words, for my students, nature is green. I think moments like this in the classroom are both important and powerful. I had a similar moment earlier in the semester when I asked my students at the beginning of the semester, in all six classes, whether the sentence “the kitchen is a political space” is a statement that makes sense to them. They were baffled by this enunciation, and in that moment I encountered something like a “gravitational anomaly” in Star Trek indicating the presence of something in space not visible to the naked eye. A moment like this indicates that each time I use the word “politics” in my classroom there is a lens through which they are hearing my words that is invisible to me. In the case of the signifier “nature” and its widespread association to all that is animate, biological, living, and green– a venerable conception of nature going all the way back to Aristotle and the title of his famous book, Physics –nature, for them, is what blooms, grows, moves, and perceives. However, this also entails that the rock, dirt, water, and the rest– all that is “inanimate” –is something other than “nature”. The surface of Mars or Jupiter is not, within this conceptual framework, nature. Insofar as the concepts we have inform our action, I believe this is a matter of deep concern, for, as the articles in Cohen’s Prismatic Ecologies argue, we must think ecology beyond green if we are to truly think ecologically. This I believe is the work of philosophy and art. We contribute, if only in a small way, to shifting conceptual assemblages in new and different directions helping in some small way to generate different ways of perceiving, acting, and living together. Our activism is both a poetic and conceptual work that helps to bring something of the buzzing confusion of being into relief.

I think moments like this in the classroom are both important and powerful. I had a similar moment earlier in the semester when I asked my students at the beginning of the semester, in all six classes, whether the sentence “the kitchen is a political space” is a statement that makes sense to them. They were baffled by this enunciation, and in that moment I encountered something like a “gravitational anomaly” in Star Trek indicating the presence of something in space not visible to the naked eye. A moment like this indicates that each time I use the word “politics” in my classroom there is a lens through which they are hearing my words that is invisible to me. In the case of the signifier “nature” and its widespread association to all that is animate, biological, living, and green– a venerable conception of nature going all the way back to Aristotle and the title of his famous book, Physics –nature, for them, is what blooms, grows, moves, and perceives. However, this also entails that the rock, dirt, water, and the rest– all that is “inanimate” –is something other than “nature”. The surface of Mars or Jupiter is not, within this conceptual framework, nature. Insofar as the concepts we have inform our action, I believe this is a matter of deep concern, for, as the articles in Cohen’s Prismatic Ecologies argue, we must think ecology beyond green if we are to truly think ecologically. This I believe is the work of philosophy and art. We contribute, if only in a small way, to shifting conceptual assemblages in new and different directions helping in some small way to generate different ways of perceiving, acting, and living together. Our activism is both a poetic and conceptual work that helps to bring something of the buzzing confusion of being into relief. This week I began teaching Adam Miller’s extraordinary and beautiful book Speculative Grace: Bruno Latour and Object-Oriented Theology for my Philosophy of Religion course. This is the third time I’ve read this surprising book, and I still find it deeply challenging both in the sense that it is difficult to pin down (I’m not sure what I was thinking by assigning it!) and in the sense that it provokes me to think deeper and harder. Composed of 41 short, sometimes cryptic, and terse chapters, Miller’s book is difficult to summarize. In many respects, I think, the book enacts one of its central claims. Things, objects, Miller says are “resistantly available”. This is his gloss on Latour’s thesis of irreduction: the real, Latour declares, is that which resists. While the thing enters into relations with other things in all sorts of ways, there is always something of the thing that resists its relations or that is irreducible to them. This is how it is with his book. There are lightning flashes of insight that render something of the book available, where relations are composed between the reader and the text, yet in its short, abbreviated formulations where examples are almost entirely absent, there is something of the book that always feels withdrawn or resistant. In this regard, the text is not only about the nature of things– in part; it is also about grace –but it also presents itself as a real thing of the universe or a force, no matter how humble. His book performs what it argues. Having known Adam now for fourteen years, this is how he himself is. He is a very quiet and dignified person, animated by a humble charisma, who discloses elements of himself in mysterious flashes, yet who you’re never quite sure you really know. He’s a singularity.

This week I began teaching Adam Miller’s extraordinary and beautiful book Speculative Grace: Bruno Latour and Object-Oriented Theology for my Philosophy of Religion course. This is the third time I’ve read this surprising book, and I still find it deeply challenging both in the sense that it is difficult to pin down (I’m not sure what I was thinking by assigning it!) and in the sense that it provokes me to think deeper and harder. Composed of 41 short, sometimes cryptic, and terse chapters, Miller’s book is difficult to summarize. In many respects, I think, the book enacts one of its central claims. Things, objects, Miller says are “resistantly available”. This is his gloss on Latour’s thesis of irreduction: the real, Latour declares, is that which resists. While the thing enters into relations with other things in all sorts of ways, there is always something of the thing that resists its relations or that is irreducible to them. This is how it is with his book. There are lightning flashes of insight that render something of the book available, where relations are composed between the reader and the text, yet in its short, abbreviated formulations where examples are almost entirely absent, there is something of the book that always feels withdrawn or resistant. In this regard, the text is not only about the nature of things– in part; it is also about grace –but it also presents itself as a real thing of the universe or a force, no matter how humble. His book performs what it argues. Having known Adam now for fourteen years, this is how he himself is. He is a very quiet and dignified person, animated by a humble charisma, who discloses elements of himself in mysterious flashes, yet who you’re never quite sure you really know. He’s a singularity. What Miller describes here, I think, is aptly formalized by the lefthand side of Lacan’s graph of sexuation. The upper portion of the equation can be read as saying “there exists a being that is the unconditioned ground of all else”, while the lower portion of the equation can be read as saying “all beings are grounded in, conditioned by, and accounted for by the agency of this being. This is a formalization of the logic of sovereignty in all its forms, or, as Miller calls them, conspiracy theories.

What Miller describes here, I think, is aptly formalized by the lefthand side of Lacan’s graph of sexuation. The upper portion of the equation can be read as saying “there exists a being that is the unconditioned ground of all else”, while the lower portion of the equation can be read as saying “all beings are grounded in, conditioned by, and accounted for by the agency of this being. This is a formalization of the logic of sovereignty in all its forms, or, as Miller calls them, conspiracy theories.