The Absent Third

It is a central thesis of Lacanian psychoanalysis that there can be no desire that is not supported by the letter (L’identification, Seminar 9, 6.12.61). Of course, Lacan’s concept of the letter will undergo a substantial evolution between 1961 and the seventies, but at this point in his development, we can simply treat the letter as the signifier. It is this special relationship between desire and language that differentiates desire from need. For if desire is different than need, then this is because desire is a relationship to an absence that can never become present. Where the privation encountered in need can be satiated and filled, desire desires only to desire. Desire maintains itself in its desire in such a way as to actively flee placing itself in a situation in which it could finally satisfy or complete itself. Here we might think of the way in which Bill Gates continuously accumulates money. It is clear that Gates’ relationship to money long ago ceased being a relationship of need. There is no amount of money that would ever satisfy Gates. Rather, we here have a ravenous desire with a limitless appetite. Gates seems to be seeking something quite different than money in his pursuit of money. Gates searches for the objet a “in” or “behind” the money. What this is could only be discerned in the course of an analysis. None of this is meant as a moral critique of Bill Gates. Desire, for everyone, is always this way. Desire is always singular and limitless.

If desire has a special relationship with the letter, then this is because only the letter sustains the possibility of absence. In order to understand this, it is first necessary to understand something of the Freudian conception of the wish. In his opus The Intepretation of Dreams, Freud had contendend that in addition to the manner in which the dream functions as a wish-fulfillment of a latent dream thought, the dream is also the expression of an eternal infantile wish around which the subject’s entire psychic life is organized. Freud is very mysterious as to the nature of this wish or how we might go about discovering it, but we can see that Lacan’s account of desire is designed to respond precisely to this question. If desire, the eternal infantile wish, can only be supported by the signifier, then this is because only the signifier can support an eternal wish. Only the signifier is capable of preserving something in its absence and through the infinite variations (substitutions) that desire undergoes in passing through its myriad substitute objects (the endless metonymy of desire).

This marks an essential difference between need and desire. There is no such thing as an eternal and persistant need, because a need disappears the moment it is satisfied. By constrast, a desire persists even when it appears to be satisfied by its object. This is the truth of the anorexic. The anorexic is the one who refuses to eat because she literally eats nothing… Which is to say the desire of the Other. The anorexic knows the manner in which food is caught up in those relations of desire belonging to the Other and seeks to express the real object of her desire or this lack embodied in the Other. She shows the difference between the demanded food (or demand to eat) and the response to the demand as an expression of love. In not eating, she symptomatically attenuates the manner in which eating itself is an expression of desire insofar as desire is the desire of the Other (the first moment of this desire being witnessed in the mother’s demand that the infant sup at her breast).

Desire thus shares a special relationship to lack or absence that is sustained through the instance of the letter. This allows us to give a very precise definition to the notion of a “complex”. A complex is a structure of desire insofar as it is sustained by a set of relations among letters. It is because something has a place that it can be missing from its place. However, having a place is a symbolic function or a function of the letter. The number on the spine of a library book marks its place within the library. This number is a letter in the Lacanian sense. If, then, desire can only be sustained by the letter, then this is because language produces the possibility of an absence or lack around which desire might circulate.

Thus we encounter one of the ways of distinguishing between reality and the real. According to the definition of the real Lacan provides in his earliest seminars, the real is that which is without lack or fissure. Another way of saying this would be to say that the real is an absolute plentitude in which nothing is out of place (since it has no place to which it belongs). At the level of the real a book can never be missing from its place because a book just always is where it is. By contrast, reality is defined by the system of places and positions inaugurated by the signifier in which lack and absence become possible. It is for this reason that Lacan claims that reality is not the real. Reality is a symbolic structure, while the real (at this point in his career) is that which is anterior to all symbolic structuration. If it is claimed that the world is a trace of language rather than language a trace of the world, this is not an idealist statement that is meant to suggest that somehow language creates matter, the planet earth, etc., but is simply the thesis that the organized experience we rely upon on a day to day basis is made possible through the agency of language that imposes an organization upon the world. Here “world” must not be thought of as the ontic object or entity “earth”, but must be thought as Heidegger thinks it as the manner in which our experience is characterized by significance, meaning or sense.

Here Deleuze, contrary to the belief of some of his enthusiasts, is thoroughly consistent with Lacan. In his masterpiece, Difference and Repetition, Deleuze argues that lack isn’t a primary term, but rather all lack is based on a prior affirmation. Lacan does not disagree with this. In order for lack to be possible, says Lacan, there must a symbolic code or network defining a system of places from which something might be lacking or out of place. This symbolic system or language is thus the affirmation upon which lack is founded.

What, then, is it about the relationship between desire and the letter that leads Lacan to claim that desire is forever cuckold by language or that the relationship between the organism and its umwelt is forever off kilter as a result of the intervention of the signifier? A man is cuckold when his wife cheats on him with another man. The wife, who is the object of his desire insofar as she is thought to return his desire, instead has a desire that lies elsewhere. Consequently, completing the analysis of the metaphor, language is to the wife as desire is to the husband. In other words, there is something about the nature of my desire that is out of step with what I seem to desire. My desire, in its dependency on language, serves ends other than those I think it serves.

There can be little doubt that Lacan’s little formulas often look like Zen koans, representing a paradox of thought which is impossible to resolve. So long as we think of language as a tool for communication, it is impossible to understand what Lacan could possibly mean by his suggestion that desire is cuckold by language. In fact, if we think of language as a mere tool used to represent our mental or psychic states, then Lacan’s entire psychoanalysis must appear completely mysterious and absurd. For this reason it is helpful to resort to analogies and metaphors to better help us locate or develop a vision of various regions of our experience that might be overlooked or ignored. Like all analogies, these analogies fail to be complete, but they have the benefit of allowing us to see something that we might not have seen before. In this respect, the relationship between a game player and an arcade game provides a nice analogy for understanding what Lacan has in mind.

When I play an arcade game such as Mortal Combat, I, the player, experience myself as simulating some great warrior (usually someone versed in martial arts or possessing a great expertise with weapons like battle axes and swords) thrown into competition with other warriors (often gorgeous, scantily clad women that are nonetheless deadly). The game provides an entire virtual space in which my virtual body is capable of things that my real body is not and in which I am allowed to do things that I would never do in day to day life. Video games give us a perfect way of thinking about the relationship between subject and object. Here the player is the subject, while all that unfolds on the screen can be understood as the object. In playing the game, the would-be warrior’s experience is thus organized in terms of a specific set of desires: namely, the desire to beat his opponent, advance levels, gain prizes and increase in strength and power, etc. Desire is thought of as what appears on the screen.

This is exactly how we tend to think of our desire in day to day life. When we speak of desire, we are speaking of either those things we want or those persons towards whom our amorous favours are directed. My desire is a desire for this or that car, for this or that book, for these clothes, etc. Similarly it is this or that person I desire or I am unsure whether I am desired by that person and so on. Just as my desire is directed towards objects and persons in day to day life, my desire is directed towards acquisition and gaining power in the realm of arcade games.

Lacan does not deny the thesis that our desire alights on objects and persons– in fact, Lacan, in seminar 5, Les formations de l’inconscient, claims that we can only arrive at knowledge of desire by tracing the metonymical shards of the object; which is to say, the manner in which desire endlessly dances from one object to the next –but complicates this thesis in a decisive and far reaching fashion. Amusingly, it is the arcade game that allows us to see this other dimension of desire that Lacan has in mind when he claims that desire is cuckold by language.

What the naive relationship to the arcade game fails to take into account is the manner in which the programming of the game moulds and structures the relationship of the player to the game. The programming of the game is the absent third mediating between the player and the events that take place in the game. As the player plays the game, all of his attention is directed towards the events taking place on the screen and the goals that he has set for himself. However, without the programming or that massive system of zero’s and one’s, the game would not take place at all.

I am not here suggesting that we need to give more respect to programmers. Rather, I am seeking to underline an analogy between the symbolic order, language or the big Other and the programming that renders the relationship of the gamer to the game possible. One feature of the programming is that it is invisible while I play the game. I do not see the zero’s and one’s or lines of code involved in the game while playing the game. These lines of code are all there, but hidden such that they seem to be taking place in another scene. When Zizek claims that the unconscious is the form of thought that is external to thought who’s ontological status is not that of thought itself, he has something like this in mind. The programming is not the actual thought of the player, but the exterior form in which that thought has to be expressed in order for the game to be played. Thus, while the player is directed towards the events on the screen, he fails to see the manner in which these events and the goals that drive his relationship to these events, are molded by the invisible code working in the background. This code or program is neither a property of the mental life of the subject (the game player) nor the events taking place in this specific instance on the screen (the object), but that which mediates and enables the relationship between the subject and object.

Perhaps the most important feature of the program as it relates to Lacan’s concept of the big Other or the symbolic order is that it cannot be changed by playing the game. No matter how poorly or how well I play Mortal Combat (and presumably I play pretty poorly), the outcome of my game fails to modify the programming of the game itself. The programming of the game remains exactly as it was before after each instance of playing the game.

This, then, gives us a glimpse of what Lacan has in mind when he claims that desire is cuckold by language. From the standpoint of my conscious experience as a subject, I naively experience my desire as being a direct relationship to an object or the other person. I fail to see the manner in which my desire is caught up in the “programming” of the culture I live in, embodied in language. I fail to see that third that intervenes between me and the object. Consequently, in pursuing my desire I am really pursuing something else. And this is unavoidable, for insofar as desire only comes into being through the intervention of language in the life of the subject, it follows that there can be no desire independent of language. Language is the absent third that mediates and informs all of my desire.

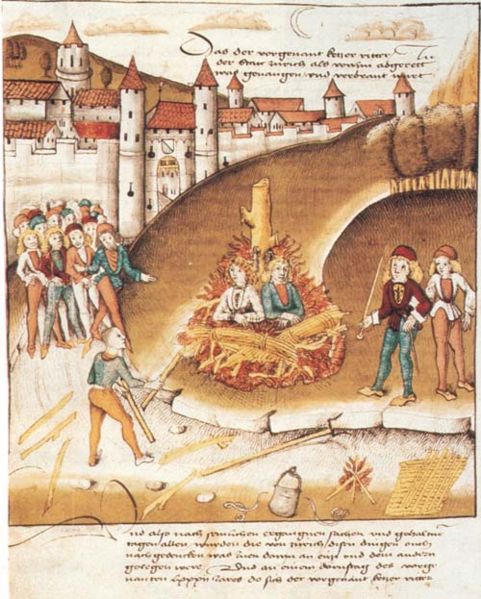

We can thus see the seriousness of Lacan’s conception of desire as it applies to our individual lives and social struggle. For if playing the game (i.e., myopically fixating on the object of my desire) leaves the nature of the game unchanged, social struggles that fixate on some particular object are doomed in their possibility of effecting real social change. If I kill the king, this might make for better social conditions under the new king, but it is still a fact that I’m playing the same game and continue to live under a Monarch. Killing the king does not get rid of the position of the king. The only real object of political struggle should be the code itself or the symbolic Order, the system of language, that informs and structures our relations to ourselves and others. But if such struggle is to be possible, then it is necessary that we become aware of that absent third, or the discourse of the Other which functions as the social unconscious.

Object-oriented social and political theory can be illustrated with respect to Lacan’s famous Borromean knots. It will be recalled that the peculiar quality of the Borromean knot is that no one of the rings is directly tied to the other, but if you cut one of the rings the other two slip away. In evoking the Borromean knot I do not here intend to give a “Lacanian reading” of object-oriented ontology. Rather, I wish to draw attention to certain features of the social and political world that object-oriented ontology would like to bring into relief for social and political theorists. Consequently, in what follows I will take a certain degree of liberty in how I use the categories of the “real”, the “symbolic”, and the “imaginary” (abbreviated “R”, “S”, and “I” respectively), only loosely associating these with Lacanian psychoanalytic categories. I will not, for example, discuss the real in the Lacanian sense as the impossible, as a constitutive deadlock, as what always returns to its place, or as constitutive antagonism. This is not because I am rejecting the Lacanian real in these senses, but rather because I am here using the Borromean knot for other purposes. I have no qualms with reintroducing concepts such as constitutive deadlocks or antagonisms at another order of analysis. In short, I am using the diagram of the Borromean knot as a heuristic device to help bring clarity to certain discussions in social and political theory.

Object-oriented social and political theory can be illustrated with respect to Lacan’s famous Borromean knots. It will be recalled that the peculiar quality of the Borromean knot is that no one of the rings is directly tied to the other, but if you cut one of the rings the other two slip away. In evoking the Borromean knot I do not here intend to give a “Lacanian reading” of object-oriented ontology. Rather, I wish to draw attention to certain features of the social and political world that object-oriented ontology would like to bring into relief for social and political theorists. Consequently, in what follows I will take a certain degree of liberty in how I use the categories of the “real”, the “symbolic”, and the “imaginary” (abbreviated “R”, “S”, and “I” respectively), only loosely associating these with Lacanian psychoanalytic categories. I will not, for example, discuss the real in the Lacanian sense as the impossible, as a constitutive deadlock, as what always returns to its place, or as constitutive antagonism. This is not because I am rejecting the Lacanian real in these senses, but rather because I am here using the Borromean knot for other purposes. I have no qualms with reintroducing concepts such as constitutive deadlocks or antagonisms at another order of analysis. In short, I am using the diagram of the Borromean knot as a heuristic device to help bring clarity to certain discussions in social and political theory.

Much to my surprise and delight, I have been exceedingly pleased by the discussion my post “

Much to my surprise and delight, I have been exceedingly pleased by the discussion my post “